This started out as an update to my post on Kanye West's song "I am a God," but wound up being nearly as long as the post itself, so I'm separating it out. But look over that first, or maybe keep it open in a separate tab.

A concern has been conveyed to me that I may have been equating rap as a lyrical form, African American English, and Kanye West in a problematic way. I wasn't really clear about my assumptions about how these three things are related, so I'll try to clarify.

So first, I definitely don't want to imply that the conventions of what is possible and not possible in rap is equivalent to the grammar of African American English. Rap is strongly identified as an African American art form such that people frequently malign hip hop as code for AAE, but as a linguist I know better than to draw similar equivalencies. As a lyrical and musical form, rap has its own conventions which aren't the same as AAE grammar. This must be the case, because speakers of other dialects and languages can produce songs which are clearly identifiable as rap!

I am assuming that Kanye West is a speaker of AAE as it spoken in Georgia, and that his phonology, as he acquired it, generates a bunch of representations. That's why I tied in the Labov, Cohen & Robins (1968) reference, to try to emphasize that these ∅ coda Go(d)s weren't just a quirk of Kanye, but rather reflective of larger dialectal trends in which Kanye is a participant. What does it matter? It's just more interesting if the reasoning I proposed here could generalize beyond just Kanye.

Next, I assume that Kanye has a personal filter, partially due to his personal taste, partially due to the conventions of rap, whereby he decides whether two words work as a rhyme. My reasoning is that if we understand Kanye's filter, and can see what comes out the other end, then we can make some assumptions about what went into it in the first place. Importantly, Kanye's rhyme filter is not AAE. In AAE, the set of words {God, Go(d), massage, ménage, garage, restaurant, croissants} definitely aren't perfect rhymes, but they all passed through Kanye's filter as rhyming equivalent.

My reasoning is as follows. All of these words passed some metric of Kanye's rhyming filter as being equivalent enough. The zero coda variant "Go(d)" is a product of Kanye's AAE phonology. If we can figure out what Kanye's filter is, then we can know something about the phonological status of "Go(d)", which can tell us something about this feature of AAE phonology. Excluding "Go(d)", all of the final syllables of the words in this rhyming scheme have 1) a low-back vowel 2) a coronal obstruent. The coronal obstruents vary quite a bit in the sub-coronal place of articulation, their manner, and in their complexity. So, I want to conclude that Kanye's filter requires matching on the vowel quality, and the major place of articulation of the coda, but not its manner or complexity.

The zero coda Go(d) is an outlier in this pattern, unless we conclude that the missing /d/ actually counts as being there. Whether or not the missing /d/ counts as being there has more to do with Kanye's phonology than his rhyming filter, and since I'm assuming Kanye's phonology comes form AAE, this could also be a property of the phonology of many AAE speakers. So, I want to conclude that it is probable that for many AAE speakers, when they produce zero coda Go(d), the /d/ still counts as being there.

Now how gone is the /d/? That's where the phonetics comes in, and the answer seems to be "very."

This is just a very general view of how to use rhyming verse to figure out something about the phonology of any language or dialect. A speaker of some language has some phonology which generates forms, and then they have a rhyming filter to see what works. By working out what the properties of the filter might be, you can try to reconstruct what the properties of the phonology is.

Thursday, June 20, 2013

Kanye's Codas and Vowels

This is just a quicky about Kanye's new song I am a God, which he collaborated on with God. The opening lyrics are:

The first thing that occurred to me was that for Kanye, [gɑ:] is rhyming equivalent to [gɑd]. That might be an interesting piece of evidence for the phonological status of these zero codas. That is, they really count as having a /d/ in them, even though it's not pronounced. Then again, I don't know if Kanye would be willing to rhyme "spa" with "God", meaning he doesn't really care about the content of coda, as long as the vowels match. Later on in the song, though, he pulls in "restaurant" and "croissant" into the same rhyming scheme, making the set of codas which are rhyming equivalent {d, ʤ, ʒ, nt, ∅}, all apical obstruents except for the zero codas. It seems like Kanye doesn't care about coda complexity, manner, or subcoronal place of articulation, but the major place of articulation does seem to matter, so I'm going to say that those ∅-codas actually count as apical obstruents for Kanye.

But, Joel Wallenberg asked me an interesting question on Twitter.

Here are the first three God's, which I heard with a [d]. They all have pretty clear formant transitions (marked by "tr"), especially the third one. (click for larger)

And here are the last 4 Gods, which I heard without a [d]. God 4 does actually have a pretty clear formant transition for an apical closure, and God 6 has something subtle going on that I'm not sure about. It looks less like a formant transition to an apical closure, and more like a return to a neutral vowel, but I've marked it "tr?" just in case. Gods 5 and 7, though, clearly don't have formant transitions to a following /d/.

So, for at least 2 out of the 4 zero coda Gods, the /d/ was really really gone.

One more interesting thing to me was that except for Gods 1 and 7, after reaching their peak F1 and F2 after the transition from [g], all of these vowels have a very steadily declining F1 and F2. In fact, I'd transcribe God 2 as being something like [gaɔ̯d]. I guess for Kanye the vowel in God is definitely long and in-gliding.

Update:

A concern has been conveyed to me that I may have been equating rap as a lyrical form, African American English, and Kanye West in a problematic way. I wasn't really clear about my assumptions about how these three things are related. I tried to clarify in this post.

I am a GodKanye pronounces the final syllable of "massage" as [ɑʤ], which caught my ear so I went back and listened more closely. By my coding, this is how Kanye produces the final consonants of each of these lines.

I am a God

I am a God

Hurry up with my damn massage

Hurry up with my damn ménage

Get the Porsche out the damn garage

I am a God

Even though I'm a man of God

My whole life in the hands of God

So y'all better quit playing with God

God: [d]Those ∅ codas mean that the /d/ was just absent. I believe AAVE deletes simple codas more often than other dialects. I don't know more recent numbers, but Labov, Cohen & Robins (1968) reported that in Harlem it happened somewhere between 5% and 20% of the times for a word like "God", depending on the context.

God: [d]

God: [d]

massage: [ʤ]

ménage: [ʒ]

garage: [ʒ]

God: ∅

God: ∅

God: ∅

God: ∅

The first thing that occurred to me was that for Kanye, [gɑ:] is rhyming equivalent to [gɑd]. That might be an interesting piece of evidence for the phonological status of these zero codas. That is, they really count as having a /d/ in them, even though it's not pronounced. Then again, I don't know if Kanye would be willing to rhyme "spa" with "God", meaning he doesn't really care about the content of coda, as long as the vowels match. Later on in the song, though, he pulls in "restaurant" and "croissant" into the same rhyming scheme, making the set of codas which are rhyming equivalent {d, ʤ, ʒ, nt, ∅}, all apical obstruents except for the zero codas. It seems like Kanye doesn't care about coda complexity, manner, or subcoronal place of articulation, but the major place of articulation does seem to matter, so I'm going to say that those ∅-codas actually count as apical obstruents for Kanye.

But, Joel Wallenberg asked me an interesting question on Twitter.

@JoFrhwld Does the vowel transition towards closure in the 0 ones, even though there's no real closure?Well, there's only one way to find out! Break out Praat!

— Joel Wallenberg (@quakerscientist) June 20, 2013

Here are the first three God's, which I heard with a [d]. They all have pretty clear formant transitions (marked by "tr"), especially the third one. (click for larger)

|

| God 1 |

|

| God 2 |

|

| God 3 |

And here are the last 4 Gods, which I heard without a [d]. God 4 does actually have a pretty clear formant transition for an apical closure, and God 6 has something subtle going on that I'm not sure about. It looks less like a formant transition to an apical closure, and more like a return to a neutral vowel, but I've marked it "tr?" just in case. Gods 5 and 7, though, clearly don't have formant transitions to a following /d/.

|

| God 4 |

|

| God 5 |

|

| God 6 |

|

| God 7 |

One more interesting thing to me was that except for Gods 1 and 7, after reaching their peak F1 and F2 after the transition from [g], all of these vowels have a very steadily declining F1 and F2. In fact, I'd transcribe God 2 as being something like [gaɔ̯d]. I guess for Kanye the vowel in God is definitely long and in-gliding.

Update:

A concern has been conveyed to me that I may have been equating rap as a lyrical form, African American English, and Kanye West in a problematic way. I wasn't really clear about my assumptions about how these three things are related. I tried to clarify in this post.

Wednesday, May 22, 2013

Socioeconomic Status and College Enrollment

There was an interesting post over at Sociological Images about the relationship between socioeconomic status and high school students likelihood of even applying to highly selective colleges.

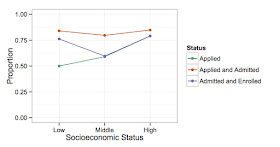

The research cited there by Alexandria Radford focused on high school valedictorians, which I think is a pretty cool way to isolate the effect of socioeconomic class. Sociological Images posted this figure from the paper (abstract? proposal?) which shows what proportion of valedictorians wind up in each category with regards to highly selective colleges

Update 2:

Of course, admission is not even half or a quarter of the battle. I don't know much about the The High School Valedictorian Project mentioned in the study, but I hope they keep tabs on the Low SES students admitted to the highly selective schools. I know the culture shock I experienced going from a good diocesan high school to an Ivy League university was pretty huge, but I don't know if it was disproportionately huge than it would have been going from any old high school to any old college, or what effect it might have on academic performance.

The research cited there by Alexandria Radford focused on high school valedictorians, which I think is a pretty cool way to isolate the effect of socioeconomic class. Sociological Images posted this figure from the paper (abstract? proposal?) which shows what proportion of valedictorians wind up in each category with regards to highly selective colleges

- They applied to at least one highly selective school.

- They were accepted to at least one highly selective school.

- They enrolled in a highly selective school.

Radford attributes the large gap between High SES valedictorians and Middle and Low SES valedictorians to reduced familiarity with highly selective schools as institutions and their admissions process. That seems to ring true to me, but I was curious how SES affects each step in this process. The graph above doesn't really tell you what proportion of Low SES students who actually applied to highly selective schools were admitted, or at least I don't believe it does. It says 42% of Low SES valedictorians were admitted to a highly selective school, but you have to apply to be admitted, and only 50% of Low SES valedictorians applied in the first place. That means that 42%/50% = 84% of Low SES students who applied were admitted. The same goes for enrollment. You have to be admitted to be enrolled, meaning the 32%/42%=76% of Low SES students who were admitted to a highly selective school also enrolled. Here's a rejiggered plot I made based on the data in the plot above.

So, it looks like to highly selective colleges' credit, the proportion of high school valedictorians who sent in applications who were then admitted is just about flat across the socioeconomic scale. 85% of High SES valedictorians who applied were admitted, and 84% of Low SES valedictorians who applied were admitted. Things look really different for enrollment though. High and Low SES students have very similar enrollment yield, (79% and 76%, respectively), but Middle SES students have much lower enrollment yield (59.6%).

I can only speculate why Middle SES students have such a lower enrollment yield than Low and High SES students. One possibility is that their family's income is just a little bit too high to qualify for needs-based scholarships. Another might be that the perceived cost-benefit ratio for Middle SES students is higher than for Low SES students.

However, I think this plot lends credence to Radford's hypothesis that reduced information and familiarity leads to reduced Low SES application rates. For Low SES valedictorians, their application rates are totally disproportionate to the probability that they will be accepted to the highly selective schools, and to the probability that they will actually attend those schools if they are accepted.

Update: I meant to include the R code for the data and plot.

Update: I meant to include the R code for the data and plot.

Update 2:

Of course, admission is not even half or a quarter of the battle. I don't know much about the The High School Valedictorian Project mentioned in the study, but I hope they keep tabs on the Low SES students admitted to the highly selective schools. I know the culture shock I experienced going from a good diocesan high school to an Ivy League university was pretty huge, but I don't know if it was disproportionately huge than it would have been going from any old high school to any old college, or what effect it might have on academic performance.

Tuesday, May 21, 2013

I Support Inclusive Scouting

This week, the Boy Scouts of America's National Council will be meeting to vote on whether the Boy Scouts should include the following statement in its membership policy for youths.

This week, the Boy Scouts of America's National Council will be meeting to vote on whether the Boy Scouts should include the following statement in its membership policy for youths.

"No youth may be denied membership in the Boy Scouts of America on the basis of sexual orientation or preference alone."I thought I would take a brief moment to publicly state my support for a more inclusive scouting, and one that will hopefully eventually welcome gay and lesbian adult leaders, and non-religious youths and leaders.

I am bothering to speak out about inclusive scouting because I believe that scouting is an over all positive experience that has great value for the youths involved in it. I outlined some of the benefits I felt that scouting had brought to my life in the letter I enclosed with my Eagle Scout award when I returned it in protest of BSA's exclusionary policies. For example, it was in the scouts that I had my first experiences with organizing with peers to reach a goal. The skills I learned there, like learning how to clearly express my vision of what should be done, how to set aside that vision in favor of ideas offered by others, and how to delegate responsibilities have been invaluable for me in my professional life. I also learned the value of living a life of principle, which is why I'm writing this blog post. I was also able to bond with my father, who is also an Eagle Scout, and my brother. I don't believe that there is any good reason to deny any youth or parent any of these experiences on the basis of their sexual orientation, gender identity, or metaphysical beliefs.

On this specific issue, I would like to preempt most objections to allowing gay youths into the scouts by coming back to the supreme court ruling that BSA won. The most most common concern I've heard voiced about allowing gay youths into the scouts revolves around who will sleep in which tent on a camping trip. Second and third most common are the discomfort other youths and sponsoring organizations may have with gay youths being in their troop.

But the majority opinion in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale made no mention of the logistics of sleeping arrangements, nor discomfort of individuals or sponsoring organizations when they decided that BSA has constitutional right to exclude gay youths. Rather, it was argued that the Boy Scouts of America had an expressive policy condemning homosexuality, that the Boy Scouts "teach that homosexual conduct is not morally straight." The constitutional right to free association that BSA won was not won on the basis of something so trivial as how tricky sleeping arrangements will be, but rather by arguing that they have a core expressive policy that being gay is wrong. When voting on whether to adopt the new membership policy, I hope that National Council members have in mind that they are voting on the principle of whether or not being gay is wrong, and that other logistical concerns are secondary.

Regarding those logistical concerns I would just briefly say that the concern I have about openly gay youths in shared tents is the real threat of violence towards the gay youths. That is the reality we are living in. Scoutmasters will have to emphasize to their troops that violence towards each other is not ok, and that we should have to treat all people with human decency, a value I should hope is well within the expressive mission of BSA. As for the discomfort of youths and sponsoring organizations at having gay youths in their troops, I would just say that one of the most valuable experiences I had in the scouts was being in a troop with some people who I would have rather not have been. Not any class of people, mind you, just individuals who at first brush I probably wouldn't have volunteered to be friends with. We don't get to choose who lives in the world with us, but we have to live and work with them every day, and hopefully we can also learn to see the value in them. I would say it is doubly important for youths brought up with religious beliefs that strongly condemn gays and lesbians to be friends with and work with gays and lesbians their own age. They are growing up in a world where gays and lesbians (fortunately) feel more comfortable being out about their orientation, and they will be forced to reconcile their religious beliefs with the fact that they will have gay and lesbian peers as adults, and they will have to do so with grace and aplomb.

I know that I haven't addressed all of the concerns people have raised about allowing gays into the Boy Scouts. For example, some people have had fairly vile things to say about gays and pedophiles which I won't bother myself with here. And I won't bother myself with any other arguments either, since most of them seem to have the property that once you provide a counter argument, a new argument can be freely generated. I think this is because these concerns about camping in tents and so on are transparently secondary to the core contention about whether being gay is wrong, a proposition which has become impolite to say itself. Hopefully, the National Council adopts the new membership policy.

Sunday, February 17, 2013

A difference between men and women.

This post was originally going to be a lot more mathy, with a bit of explanation about the source-filter model of speech production with an aside about dead dog heads mounted on compressed air tanks thrown in there, and a whole description of my methods, but I felt like I was sort of burying the lede there. Instead, I'm focusing more on how people are interested in magnifying the difference between men and women.

It started off with me estimating the vocal tract lengths of the speakers in the Philadelphia Neighborhood Corpus. Given sufficient acoustic data from a speaker, and making some simplifying assumptions, and taking into account the acoustic theory of speech, you can roughly estimate how long a person's vocal tract (meaning distance from vocal cords to lips) is. I went ahead and did this for the speakers in the PNC, and plotted the results over age.

Pretty cool, right? There's nothing especially earth shattering here. It's known that men, on average, have longer vocal tracts than women. I was a little bit surprised by how late in age the bend in the growth of vocal tracts were.

Here's the density distribution of vocal tract lengths for everyone over 25 in the corpus.

That's a pretty big effect size. Mark Liberman has recently posted about the importance of reporting effect sizes. He was focusing on how even though people are really obsessed with cognitive differences between men and women, the distributions of men and women are almost always highly overlapping.

Following Mark on this, I went ahead and calculated Cohen's-d for these VTL estimates.

So, 1.71 is a fairly large Cohen's-d effect size. I had heard that the difference in vocal tract length between men and women was disproportionately large given just body size differences. I managed to find some data on American male/female height differences, but the effect size is not impressively smaller than the VTL effect size (1.64, about 95% the VTL effect size).

Compared to the effect that Mark was looking at (science test scores), these effect sizes are enormous. The effect size of height between men and women is about 23 times larger than the science test score differences which warranted a writeup in the New York Times.

And in another post, they provide this picture of a reporter being comically boosted to appear taller than the woman he's interviewing.

My take away point is that when it comes to socially constructing large and inherent differences between men and women, even the largest statistical difference there is out there is still not good enough for people, and needs to be augmented and supported. Then take into account that most other psychological and cognitive differences have drastically smaller effect sizes, and it really brings into focus how the emphasis on gender differences must draw almost all of its energy from social motivations, rather than from evidence or data or facts.

It started off with me estimating the vocal tract lengths of the speakers in the Philadelphia Neighborhood Corpus. Given sufficient acoustic data from a speaker, and making some simplifying assumptions, and taking into account the acoustic theory of speech, you can roughly estimate how long a person's vocal tract (meaning distance from vocal cords to lips) is. I went ahead and did this for the speakers in the PNC, and plotted the results over age.

Pretty cool, right? There's nothing especially earth shattering here. It's known that men, on average, have longer vocal tracts than women. I was a little bit surprised by how late in age the bend in the growth of vocal tracts were.

Here's the density distribution of vocal tract lengths for everyone over 25 in the corpus.

That's a pretty big effect size. Mark Liberman has recently posted about the importance of reporting effect sizes. He was focusing on how even though people are really obsessed with cognitive differences between men and women, the distributions of men and women are almost always highly overlapping.

Following Mark on this, I went ahead and calculated Cohen's-d for these VTL estimates.

So, 1.71 is a fairly large Cohen's-d effect size. I had heard that the difference in vocal tract length between men and women was disproportionately large given just body size differences. I managed to find some data on American male/female height differences, but the effect size is not impressively smaller than the VTL effect size (1.64, about 95% the VTL effect size).

Compared to the effect that Mark was looking at (science test scores), these effect sizes are enormous. The effect size of height between men and women is about 23 times larger than the science test score differences which warranted a writeup in the New York Times.

Yet, still not big enough.

As I was thinking about how height difference is perhaps one of the largest statistical differences between men and women, it also struck me how often it is still not big enough for social purposes. Sociological Images has a good blog post about how even though Prince Charles was about the same height, if not shorter than Princess Diana, in posed pictures he was posed to look much taller than her. Here's an example of them on a postage stamp:And in another post, they provide this picture of a reporter being comically boosted to appear taller than the woman he's interviewing.

My take away point is that when it comes to socially constructing large and inherent differences between men and women, even the largest statistical difference there is out there is still not good enough for people, and needs to be augmented and supported. Then take into account that most other psychological and cognitive differences have drastically smaller effect sizes, and it really brings into focus how the emphasis on gender differences must draw almost all of its energy from social motivations, rather than from evidence or data or facts.

Thursday, February 7, 2013

I recommend Lexicon Valley

Perhaps the most frustrating thing about being a linguist is the enormous gap among educated people about how little they actually know about language, and how confident they are that they know a lot about language. If you keep up with this blog, I spend a lot of time venting this frustration here (etc. etc. etc.).

But I didn't start blogging in order to complain about how other people are getting it wrong. I started blogging to have an informal outlet for passion for linguistics! I've been a little concerned about the negative tone of a few of my recent posts, so here's a more positive one.

But... it does start off with a complaint. At the LSA this year, David Pesetsky's plenary focused on the failure of linguistics (and more specifically, generative linguistics) to penetrate the popular science press. Instead, stories about physicists discovering the most common English word is "the," and psychologists arguing that structure of language is really words like beads on a string get a lot more play. At the Q&A, Ray Jackendoff made the point that there is a folk linguistics that is intricately tied up in social politics that acts as a major roadblock to the popular advancement of real linguistic research. I've said similar things before.

What is to be done about this state of affairs is the topic of another blog post. Right now, I'd like to bring attention to a bright light of potential linguistics popularization.

Lexicon Valley is a podcast hosted by Slate. I've been listening to it off and on since it started, and I have to say I've always enjoyed it. The hosts play two roles in a dialectic. Mike Vuolo is the patient intellectual, and I've always been impressed by the background research he's done. Bob Garfield is the voice of the untutored establishment, and, well, I think that description adequately sums up my opinion of what he brings to the show. It's actually an important role he plays, because without a vocal foil, Vuolo's research would lie rather flat. It's also important for the cause of linguists to have people hear brash knee jerk reactions rebuked by careful research.

They have covered a few topics I know a little bit about, and I've always started listening to each show bracing myself for frustration and disappointment. It's a learned reaction I have from every other discussion of language in popular media. But Lexicon Valley usually carries through for me. They've done great shows on African American English, grammatical gender, and the English epicene pronoun, speaking to actual linguists in each case, and most recently they've just done a really good portrayal of Labov's department store study (Part 1,Part 2).

They did catch a lot of flack recently for their show on creaky voice. I was so nervous when I started listening to it, because the recent coverage creaky voice has gotten has been worse than terrible. Per usual, though, Vuolo's research and discussion were excellent. Garfield, on the other hand, spouted some really negative attitudes, and I think he deserves every criticism of sexism that he got. Even within the dialectic of the show, Garfield brought a net negative contribution that time round. On the subsequent show, though, Vuolo read out some pretty harsh commentary about Garfield. Garfield offered a nonpology (something about how he can't be sexist, he has daughters), but it was good to have some of the criticism read out loud.

On average, modulo Garfield's frustrating attitudes, I would highly recommend the podcast, and would recommend recommending the podcast.

While I think Lexicon Valley has done some great work so far, I don't think it has yet provided coverage of linguistics in quite the way Pesetsky dreams of. So far, they've mostly covered topics that are reactive to popular gripes or misconceptions about language. In some respect, it'd be hard for them to do otherwise, because the popular understanding of language science is far below that of almost any natural science, or so it seems from this angle.

I hope, though, that they might find a way to approach linguistic topics which are not just reactive. Just addressing the idea that there are functional elements which have no phonological realization would be enormous. Garfield could play the skeptic, believing that what you see is what you get.

So linguists, listen in, get a feel for the show, and maybe if you have a topic which could be nicely formatted into a 20 minute conversation, send it in to them!

But I didn't start blogging in order to complain about how other people are getting it wrong. I started blogging to have an informal outlet for passion for linguistics! I've been a little concerned about the negative tone of a few of my recent posts, so here's a more positive one.

But... it does start off with a complaint. At the LSA this year, David Pesetsky's plenary focused on the failure of linguistics (and more specifically, generative linguistics) to penetrate the popular science press. Instead, stories about physicists discovering the most common English word is "the," and psychologists arguing that structure of language is really words like beads on a string get a lot more play. At the Q&A, Ray Jackendoff made the point that there is a folk linguistics that is intricately tied up in social politics that acts as a major roadblock to the popular advancement of real linguistic research. I've said similar things before.

What is to be done about this state of affairs is the topic of another blog post. Right now, I'd like to bring attention to a bright light of potential linguistics popularization.

Lexicon Valley

Lexicon Valley is a podcast hosted by Slate. I've been listening to it off and on since it started, and I have to say I've always enjoyed it. The hosts play two roles in a dialectic. Mike Vuolo is the patient intellectual, and I've always been impressed by the background research he's done. Bob Garfield is the voice of the untutored establishment, and, well, I think that description adequately sums up my opinion of what he brings to the show. It's actually an important role he plays, because without a vocal foil, Vuolo's research would lie rather flat. It's also important for the cause of linguists to have people hear brash knee jerk reactions rebuked by careful research.

They have covered a few topics I know a little bit about, and I've always started listening to each show bracing myself for frustration and disappointment. It's a learned reaction I have from every other discussion of language in popular media. But Lexicon Valley usually carries through for me. They've done great shows on African American English, grammatical gender, and the English epicene pronoun, speaking to actual linguists in each case, and most recently they've just done a really good portrayal of Labov's department store study (Part 1,Part 2).

They did catch a lot of flack recently for their show on creaky voice. I was so nervous when I started listening to it, because the recent coverage creaky voice has gotten has been worse than terrible. Per usual, though, Vuolo's research and discussion were excellent. Garfield, on the other hand, spouted some really negative attitudes, and I think he deserves every criticism of sexism that he got. Even within the dialectic of the show, Garfield brought a net negative contribution that time round. On the subsequent show, though, Vuolo read out some pretty harsh commentary about Garfield. Garfield offered a nonpology (something about how he can't be sexist, he has daughters), but it was good to have some of the criticism read out loud.

On average, modulo Garfield's frustrating attitudes, I would highly recommend the podcast, and would recommend recommending the podcast.

Could it be better?

While I think Lexicon Valley has done some great work so far, I don't think it has yet provided coverage of linguistics in quite the way Pesetsky dreams of. So far, they've mostly covered topics that are reactive to popular gripes or misconceptions about language. In some respect, it'd be hard for them to do otherwise, because the popular understanding of language science is far below that of almost any natural science, or so it seems from this angle.

I hope, though, that they might find a way to approach linguistic topics which are not just reactive. Just addressing the idea that there are functional elements which have no phonological realization would be enormous. Garfield could play the skeptic, believing that what you see is what you get.

So linguists, listen in, get a feel for the show, and maybe if you have a topic which could be nicely formatted into a 20 minute conversation, send it in to them!

Sunday, February 3, 2013

Does language "cool"?

A few months ago, I posted about how I was relatively unimpressed by a paper arguing that the observed Zipfian distribution of words in a corpus is due to "preferential attachment" aka the Matthew Effect aka the rich get richer. The author of that paper is apparently also a co-author of a paper called "Languages cool as they expand: Allometric scaling and the decreasing need for new words." The writeup in Inside Science summarizes it like this:

This "language is words" axiom is part of most people's folk linguistics that we have to train people out of when they take Intro to Linguistics. That's why it's a little hard to take the work of these physicists seriously at first glance. It is as if they were trying to write a serious paper on biological evolution with the assumption that traits acquired by an organism during its life were inheritable.

But there is an aspect of linguistic knowledge relating to the set of words and morphemes a speaker knows, which linguists call the "lexicon". So, I'll just go ahead and reread the paper mentally replacing each instance of "language" with "lexicon" in order to get through it.

The key problem that I see with the paper is the conflation of "new to the corpus" and "new to the lexicon." Here's how the problem of sampling language was describe to me, and I believe it goes back to Good (1953) and is key to Good-Turing Smoothing. Say you are a entomologist working in a rain forest, trying to make a survey of insect life. You put out your net for a night to collect a sample, then count up all the species in your net. Some bug species are going to be a lot more frequent than others. You'll have some species that show up many times in the net, but even more species will show up in the net with only one member. Now, let's say that you come back to the same rain forest two years later, and repeat the sample. You are nearly guaranteed to observe new species in your net this time around, but the key question is whether they are just new to the net, or are they new to the rain forest. If they're new to the rain forest, did they migrate in, or are they hybrids of two other species, or has a species you saw previously evolved really rapidly so that you're seeing it as different now?

These are really interesting and important questions for our entomologist to answer, but you cannot arrive at a definitive answer based simply on the fact that this new species has now showed up in your net. In fact, depending on a few factors, the answer with the highest probability is that the new species is simply new to your net. The Good-Turing estimate of the probability that the very next bug you catch will be a new species is that it's roughly equivalent to the proportion of bugs you've already caught that belong to a species you've only seen once.

The situation gets even more confusing if you come back to the same rain forest two years later with a net twice the size.

The paper has a figure plotting the increase in lexicon size over time. My first thought when I saw it was that it must be the case that the overall size of the corpus at each time point must also be going up. Coming back to the entomologist in the rain forest, the number of species in his net is merely a sample of how many species there are in forest. In the same exact way, the number of words in a lexicon can only be estimated by the words which people happened to write down. As you increase the size of the net, you're going to find more species which were already in the forest, but not in your net. As you increase the size of your corpus, you're going to find more words which were already in the lexicon, but not in the corpus.

Now, you need to add to this that at any given point in time, the true maximum number of possible words you could potentially observe in any given language is ∞. Yes, in fact, the whole reason language is interesting to study is because given a finite set of mental objects, and a finite set of operations to combine them, you can come up with an infinite set of stings, and that goes for words too, not just sentences. In 1951, "iPod" was a possible word of English, it just wasn't used, or at least not for the same purpose it is now.

Regarding the question of whether the "active" (as I'll call it) lexicons of languages have grown over the past 200 years, well, indeed, the overall number of printed words has also increased. Almost all of their results seem to have more to do with the technological development of publishing than it does with any other linguistic or cultural development. It is as if the entomologist said that over the past decade, the biodiversity in his rainforest has exploded, when really what's going on is his nets have been getting progressively larger.

Now, it might be the case that the active lexicon has grown more than would be expected given the increase in the size of the corpus year over year, but as far as I can tell, the authors did not try to estimate whether this was the case.

Again, though, the frequency, even relatively frequency, of a word in a corpus is merely an estimate of its true frequency. As the size of the corpus increases, so should the reliability of its frequency estimates, and we would predict decreasing volatility of those frequency estimates. The authors check for this, and find exactly this relationship between corpus size and frequency volatility, but I can't tell whether there was excess "cooling" left over. I wish they had said, "there was x proportion of cooling left unaccounted for by simply accounting for the size of the corpus," but I think this is perhaps another symptom of the assumption that the corpus=the lexicon=the language that I complained about before.

[A] recent analysis has found that as a language grows over time, it becomes more set in its ways. New words are always being added, according to this study, but few become widely used and part of the standard vocabulary.My linguist hackles immediately raised at this statement, and that's because there is a large and fundamental difference between what a linguist understands the term "language" to refer to, and what the authors of the column and paper understand it to refer to. What the physicists and the reporter mean by "language" is roughly "a set of words," and in the context of the paper, they almost seem to mean "the set of words which have been published."

This "language is words" axiom is part of most people's folk linguistics that we have to train people out of when they take Intro to Linguistics. That's why it's a little hard to take the work of these physicists seriously at first glance. It is as if they were trying to write a serious paper on biological evolution with the assumption that traits acquired by an organism during its life were inheritable.

But there is an aspect of linguistic knowledge relating to the set of words and morphemes a speaker knows, which linguists call the "lexicon". So, I'll just go ahead and reread the paper mentally replacing each instance of "language" with "lexicon" in order to get through it.

Overall Thoughts

This paper seems to be a relatively competent (modulo Mark Liberman's concerns about OCR errors) description of the statistical properties of large corpora. But that's really as far as I think any of the claims can go. I am totally unconvinced that their results shed any light on language change, development, evolution, etc. I'm not even sure that the simplest statement that "the lexicon of languages has grown over the past 200 years" can be supported by the results reported.The key problem that I see with the paper is the conflation of "new to the corpus" and "new to the lexicon." Here's how the problem of sampling language was describe to me, and I believe it goes back to Good (1953) and is key to Good-Turing Smoothing. Say you are a entomologist working in a rain forest, trying to make a survey of insect life. You put out your net for a night to collect a sample, then count up all the species in your net. Some bug species are going to be a lot more frequent than others. You'll have some species that show up many times in the net, but even more species will show up in the net with only one member. Now, let's say that you come back to the same rain forest two years later, and repeat the sample. You are nearly guaranteed to observe new species in your net this time around, but the key question is whether they are just new to the net, or are they new to the rain forest. If they're new to the rain forest, did they migrate in, or are they hybrids of two other species, or has a species you saw previously evolved really rapidly so that you're seeing it as different now?

These are really interesting and important questions for our entomologist to answer, but you cannot arrive at a definitive answer based simply on the fact that this new species has now showed up in your net. In fact, depending on a few factors, the answer with the highest probability is that the new species is simply new to your net. The Good-Turing estimate of the probability that the very next bug you catch will be a new species is that it's roughly equivalent to the proportion of bugs you've already caught that belong to a species you've only seen once.

The situation gets even more confusing if you come back to the same rain forest two years later with a net twice the size.

The paper has a figure plotting the increase in lexicon size over time. My first thought when I saw it was that it must be the case that the overall size of the corpus at each time point must also be going up. Coming back to the entomologist in the rain forest, the number of species in his net is merely a sample of how many species there are in forest. In the same exact way, the number of words in a lexicon can only be estimated by the words which people happened to write down. As you increase the size of the net, you're going to find more species which were already in the forest, but not in your net. As you increase the size of your corpus, you're going to find more words which were already in the lexicon, but not in the corpus.

Now, you need to add to this that at any given point in time, the true maximum number of possible words you could potentially observe in any given language is ∞. Yes, in fact, the whole reason language is interesting to study is because given a finite set of mental objects, and a finite set of operations to combine them, you can come up with an infinite set of stings, and that goes for words too, not just sentences. In 1951, "iPod" was a possible word of English, it just wasn't used, or at least not for the same purpose it is now.

Regarding the question of whether the "active" (as I'll call it) lexicons of languages have grown over the past 200 years, well, indeed, the overall number of printed words has also increased. Almost all of their results seem to have more to do with the technological development of publishing than it does with any other linguistic or cultural development. It is as if the entomologist said that over the past decade, the biodiversity in his rainforest has exploded, when really what's going on is his nets have been getting progressively larger.

Now, it might be the case that the active lexicon has grown more than would be expected given the increase in the size of the corpus year over year, but as far as I can tell, the authors did not try to estimate whether this was the case.

What about this cooling down?

The "cooling" effect referred to by the paper is the suggestion that as a language "grows" (which as I just said is dubious), the frequency with which particular words are used becomes more stable. Some words are more frequent than others, but words are less likely to move up and down in frequency over time/as the lexicon grows. Back to entomology, the suggestion is that as more species cram into a rainforest, each species is less likely to become more or less populous.Again, though, the frequency, even relatively frequency, of a word in a corpus is merely an estimate of its true frequency. As the size of the corpus increases, so should the reliability of its frequency estimates, and we would predict decreasing volatility of those frequency estimates. The authors check for this, and find exactly this relationship between corpus size and frequency volatility, but I can't tell whether there was excess "cooling" left over. I wish they had said, "there was x proportion of cooling left unaccounted for by simply accounting for the size of the corpus," but I think this is perhaps another symptom of the assumption that the corpus=the lexicon=the language that I complained about before.